"The role of regulation is important because absent regulation, nobody would pay for carbon emissions or pay a penalty for emitting carbon. So, almost by definition, government has to create the market, set the rules, enforce penalties, set a carbon cap." – The Economist

The latest iteration of the global conference on climate change came to an end earlier this month. The event, better known as COP26, featured a lineup of A-list celebrities including Sir David Attenborough, Maisie Williams, Ellie Goulding, and Matt Damon.

The star-studded guest list highlighted how popular it has become to be a proponent of climate change mitigation. In the eyes of today's society, it has never been sexier to care about climate change.

Leonardo DiCaprio, who was also in attendance, is a perfect example of that reality.

But decarbonizing the global economy isn't going to be a sexy process. Instead, it'll require a healthy dose of hard work, painstakingly long and thankless hours, as well as government regulations and incentives.

Unsexy brings me to today's topic of discussion: Carbon Border Adjustment Taxes (or CBAT for short).

Unbeknownst to most, including myself until recently, the European marketplace for carbon emissions has been undergoing massive changes in the past several years. Earlier this year, those changes culminated in the EU announcing their proposal of a carbon tariff on goods imported into the 28-country trading block.

If implemented, this update to Europe's carbon pricing scheme would be the first of its kind globally. I also believe that it has the potential to be a huge step forward in reducing global emissions.

To understand the relevance of this obscure CBAT thingamajig, it's worth exploring a few questions. What exactly are carbon taxes? How do these things work? And what purpose are they intended to serve?

Buckle up.

This week's edition of the Plug has five sections:

🥕 Cap & Trade for Climate Change

🌎 A Global Patchwork of Systems

🚬 Exporting Our Carbon Emissions

🏃♀️ International Leaders & Laggards

✈️ Emissions to Save the Planet

🥕 Cap & Trade for Climate Change

At the most superficial level, the intention behind a carbon tax is to make it less expensive for companies to invest in decarbonization today, rather than to continue generating carbon emissions into the future.

The world derives many benefits from its energy consumption, including from the energy generated by burning fossil fuels. Those benefits are, in part, valued in the price we pay for different energy sources:

At the gas station, while we fill up our cars and trucks

Encompassed in our plane tickets which are reliant on jet fuel

In our electricity bills, to heat and cool our homes

.

But the costs borne by both our planet and by humanity that result from carbon emissions? Historically, those costs haven't been factored into the price we pay for the privilege of cheap, reliable energy supply.

The health effects of air pollution and the impacts of climate change are two of the most obvious societal costs of energy consumption. These are otherwise referred to as negative externalities. In a perfect world, I believe that emitters should be responsible for paying for the negative externalities they create.

The purpose of a carbon tax is to begin pricing negative externalities into our energy supply.

The most common form of a carbon tax (and the easiest for me to explain) is a system known as cap-and-trade. In a cap-and-trade system, carbon taxes create both an incentive (think carrot) for reducing emissions now and a penalty (think stick) for failing to do so.

The video below, produced by The Economist, does a better job than I ever could of explaining how that system functions.

But if you're too busy to watch that video, don't stress! My cliff notes on the inner workings of cap-and-trade systems are as follows:

A governing body sets a ceiling (or cap) on the volume of carbon emissions that companies can emit annually

The governing entity will either give out or sell permits that allow companies to generate emissions up to that specified level

The ceiling differs by company, based on size, industry and other factors

Over time, the ceiling on carbon emission begins to decrease, and fewer emission permits are issued; in theory, this should increase the price of emissions year over year

For companies that decarbonize quickly, excess emission permits can be sold to other companies that have not been successful in sufficiently reducing emissions

If a company emits more than is permitted under the defined emissions cap, it faces a fine for its non-compliance

.

The European Union currently has such a system in place. And within that system, there is a going price for the ability to generate emissions.

That price has risen by over 100% since the beginning of this year.

The rise in European carbon prices is a sign that their system is working; it's becoming more expensive for companies to emit. Although, admittedly, a year-long timeframe is too short to draw any bulletproof conclusions.

Time will be the ultimate determinant of Europe's ability to regulate emissions.

That all sounds relatively simple, right?

While a cap-and-trade system might sound simple in theory, I understand that establishing and maintaining such a program is much more complicated in practice. But I am also increasingly of the belief that the hassle involved in setting up and enforcing such a system is worth the effort.

Even if carbon markets and cap-and-trade programs aren't sexy…

🌎 A Global Patchwork of Systems

There is, however, one significant problem with global carbon pricing: the world can't seem to agree on one specific plan.

What a surprise!

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently called for the creation of a "global" carbon market. But as it currently standards, the state of carbon markets globally are both hyper-localized and bespoke in structure.

Each system has its own rules. Each one has an independent price for carbon emissions. And the disconnected patchwork of localized regulation is inconsistent across borders.

The result is a hodgepodge of different systems that aren't designed to interact with one another. Which is problematic, given the interconnected nature of our global economy.

As I understand it, the European Union currently has the most comprehensive carbon pricing scheme of any region in the world. Canada, and my home province of British Columbia specifically, also seem to be doing a pretty good job on this front.

On the other hand, the U.S. still does not have a national carbon price. Because, well, that would involve Democrats and Republicans reaching an agreement.

God knows that's not going to happen anytime soon.

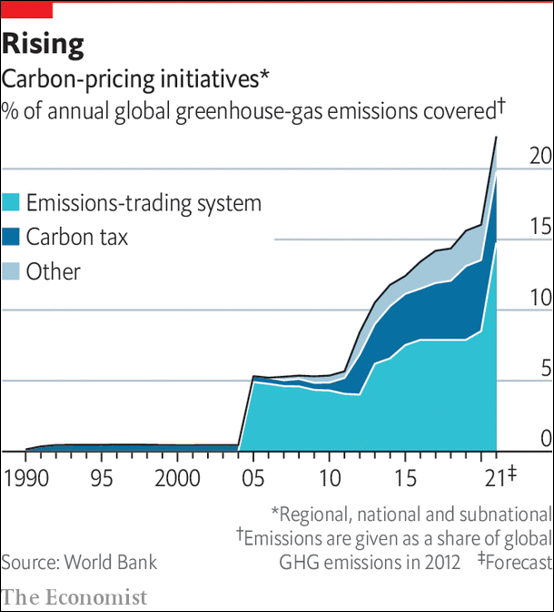

Even though the developed world has seen sporadic successes in the establishment of domestic carbon markets, most emissions globally remain untaxed. The percentage of global greenhouse gas emissions covered by carbon pricing schemes today remains barely above 20%.

The world has a long way to go in reaching a consensus on emission taxation. But the green shoots of progress are slowly beginning to show up.

🚬 Exporting Our Carbon Emissions

The are repercussions to the world’s inability to create a coherent global carbon pricing scheme. Without consistency in carbon price regulation across countries, we face the potential risk of carbon leakage: a concept that is worth explaining both at a company- and country-specific level.

Company-Specific: Carbon leakage is the corporate decision to reroute its supply chain through countries with less stringent regulations on carbon emission to maximize its profit.

Country-Specific: Carbon leakage is the rise in emissions in one country resulting from emission reductions in another country with stricter carbon pricing.

A company's ability to work around a carbon pricing scheme by simply redomiciling part of its supply chain negates its effectiveness. Instead of global emission reductions, companies are incentivized to relocate their operations to regions with relaxed (or ideally non-existent) carbon pricing policies.

It's a rat race to the bottom of emission regulations!

This is where a Carbon Border Adjustment Tax (CBAT) comes into play. The idea behind a CBAT is to create a level playing field for companies that operate in one specific geography, but that may have different supply chains.

If effective, it would reduce (or eliminate) the incentive for companies to reshuffle supply chains to skirt decarbonization.

By virtue of the fact that supply chains are globally interconnected, emission-intensive products are imported and exported between countries. That reality distorts country-specific emission levels.

The European CBAT proposal is to incorporate consideration for the emission intensity of products moving across international borders through a tax or tariff.

I believe that innovative schemes that incorporate the cost of carbon across supply chains, like the one proposed by the European Union, are essential to incentivize global decarbonization. Otherwise, the countries and companies striving for leadership in carbon emission reductions will only get punished for their initiative.

The conflicting challenge will be to understand the impact of these systems on less developed countries that may not yet be in a position to prioritize decarbonization. This tradeoff between decarbonization and the alleviation of energy poverty globally is incredibly complex and nuanced.

I don't envy the policymakers trying to sort through all this complexity. But I do admire the work that they're doing behind the scenes to create meaningful decarbonization opportunities.

🏃♀️ International Leaders & Laggards

The European Union’s announcements this year ruffled geopolitical feathers.

Outside of the EU, several countries (America included) expressed their disapproval of the potential implementation of a CBAT. The EU's announcement, alongside its leadership in decarbonization, will create ripple effects through global supply chains and alter the competitive dynamics between companies as well as the countries in which they choose to domicile themselves.

The analysis below by Bloomberg Economics does a fantastic job of highlighting Europe’s rationale behind the CBAT announcement. It also makes clear why the international community reacted with frustration.

For countries leading the decarbonization push, there are a handful of negative economic repercussions that would result from their leadership in the absence of trade protections (such as a CBAT). Similarly, decarbonization laggards could be net economic beneficiaries from their lack of proactivity.

There is a competitive disadvantage inherent in the pursuit of Net Zero objectives. Partly because the negative externalities of carbon emission have not previously been taken into account. For countries to show leadership in decarbonizing their economies puts them at an inherent competitive disadvantage.

The chart below highlights that for countries who are early movers on the decarbonization front, that trade protections (including carbon tariffs) will define whether their economic trajectory is positively or negatively affected.

From what I understand, rules governed by the World Trade Organization make it challenging to restrict international trade in any way. That means that climate-specific exemptions would need to be created to accommodate a border tax.

The EU's announcement is interesting because it's the first of its kind. And because it creates an incentive for countries trading with the European Union to pursue decarbonization. Otherwise, they or risk being punished for their inaction.

Without such action, in the presence of international carbon schemes, heavy emitting countries will continue to lose out on global trade opportunities.

✈️ Emissions to Save the Planet

I'm most interested in watching whether or not other countries choose to follow Europe's lead. And, more broadly, how carbon markets evolve globally in the decades to come.

In the past, the obvious shortcoming of carbon markets is that the price of emissions has been too low to motivate change. Some economists have estimated that the cost of carbon would need to be closer to $100 worldwide by 2030 to achieve the targets laid out in the Paris Agreement. For reference, as of 2020, carbon prices in Canada ranged from US$15.00–30.00.

As it currently stands, there is no carbon market globally that has a carbon price anywhere near that specified $100-level.

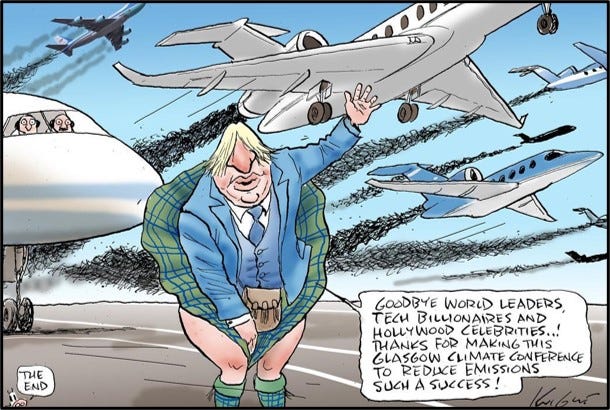

There was plenty of negativity that came out of COP26. A few examples where headlines featured the term "failure" can be found here, here and here. And I don't deny that there's an irony in the excess emissions generated by all of the private jets on which international attendants arrived in Glasgow.

But as I’ve tried to emphasize, decarbonizing our economies isn't going to be a sexy process. And so, at times, the most meaningful headlines won't necessarily appear on the front page.

Such is the example of Europe's CBAT.

Very well written and balanced piece Adam, well done. This section caught my eye:

"The conflicting challenge will be to understand the impact of these systems on less developed countries that may not yet be in a position to prioritize decarbonization. This tradeoff between decarbonization and the alleviation of energy poverty globally is incredibly complex and nuanced."

The fact that this tension exists belies the simplified claim that 'climate change means jobs', which gets banded around in mainstream discourse. Sure, jobs will be created building wind farms and decommissioning oil rigs. But what about existing jobs in poorer countries that export carbon-intensive manufactured goods to the EU? A 'just' energy transition must somehow protect or replace these, not cut the most vulnerable workers loose.

The points you make about the WTO exemptions are spot on, and that Bloomberg chart visualises the problem brilliantly. This all begs the question: Is there an historical example of border taxes leading to a unified global response to a common threat? I am not aware of one.