I was fortunate to spend most of this summer back home in Vancouver.

During that time, I began reaching out to Canadian energy businesses to learn more about what they do. One local company was particularly interesting.

It’s not really an energy business, though… It’s more “anti-emissions.”

Carbon Engineering (CE) is based out of Squamish, British Columbia. The company is focused on developing technology that captures carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere, at a megaton-scale. In fact, each CE facility would be able to capture the CO2 equivalent of ~40 million trees.

This technology is referred to as Negative Emission Technology (NETs1). Which is the topic we’re exploring today.

This week’s edition has 5 sections:

Houston, We Have a Carbon Problem 📈

The Holy Grail: Negative Emissions 👼

Our Drive to Decarbonize 🚬

How to Stop Our Ship from Sinking 🚢

The Many Different Paths to Zero 🚶

Houston, We Have a Carbon Problem 📈

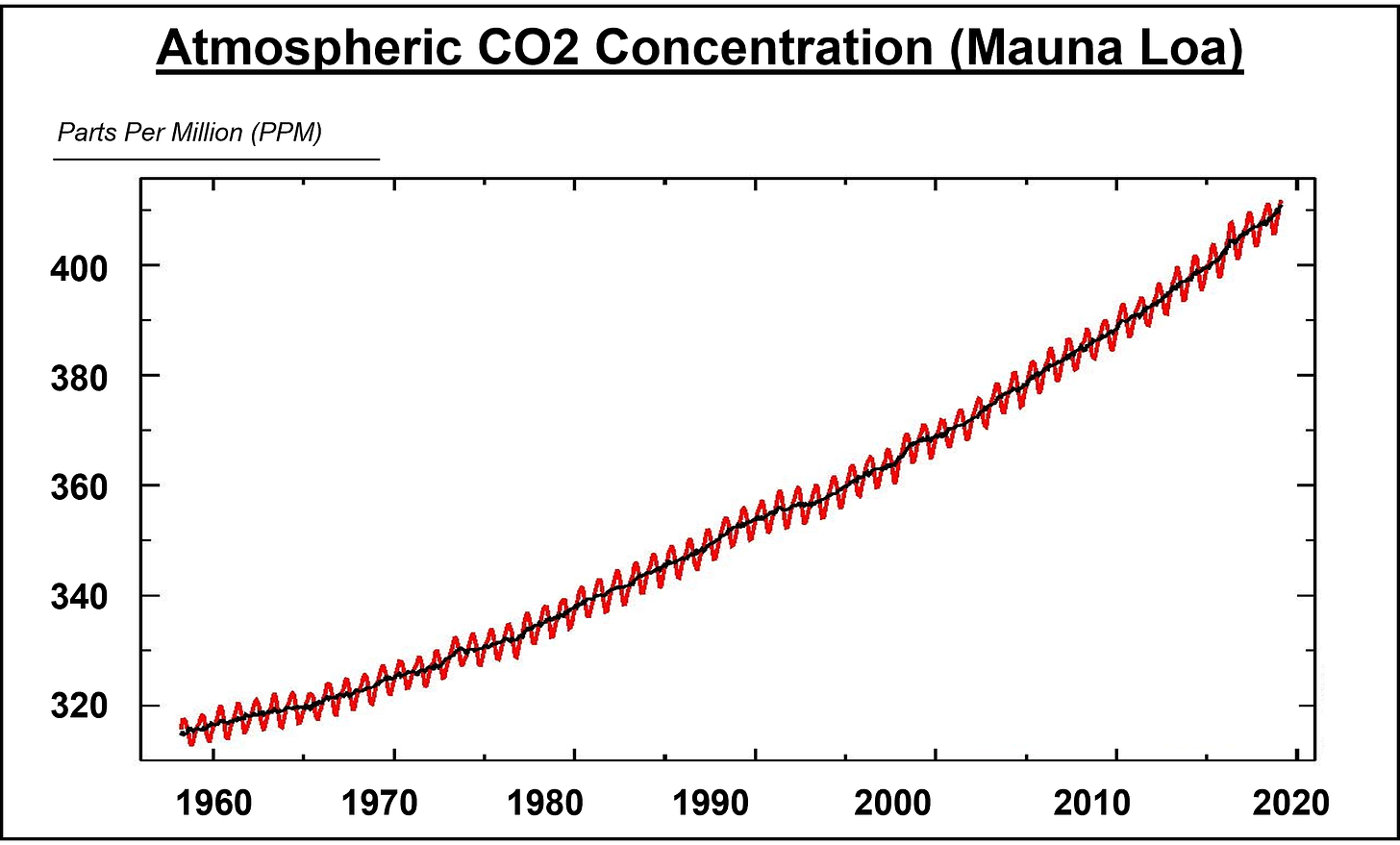

Since 1959, the NOAA2 (U.S. government agency) has been measuring the concentration of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere. For simplicity, I’ll refer to this metric going forward as either “carbon dioxide concentration” or “CO2 concentration”.

Earlier this year, the NOAA announced that CO2 concentration hit a new high watermark.

Obviously, that’s not a great sign…

The chart heeds an important warning.

Without making meaningful changes to the way humans live; we can expect CO2 concentration to continue rising in the decades to come.

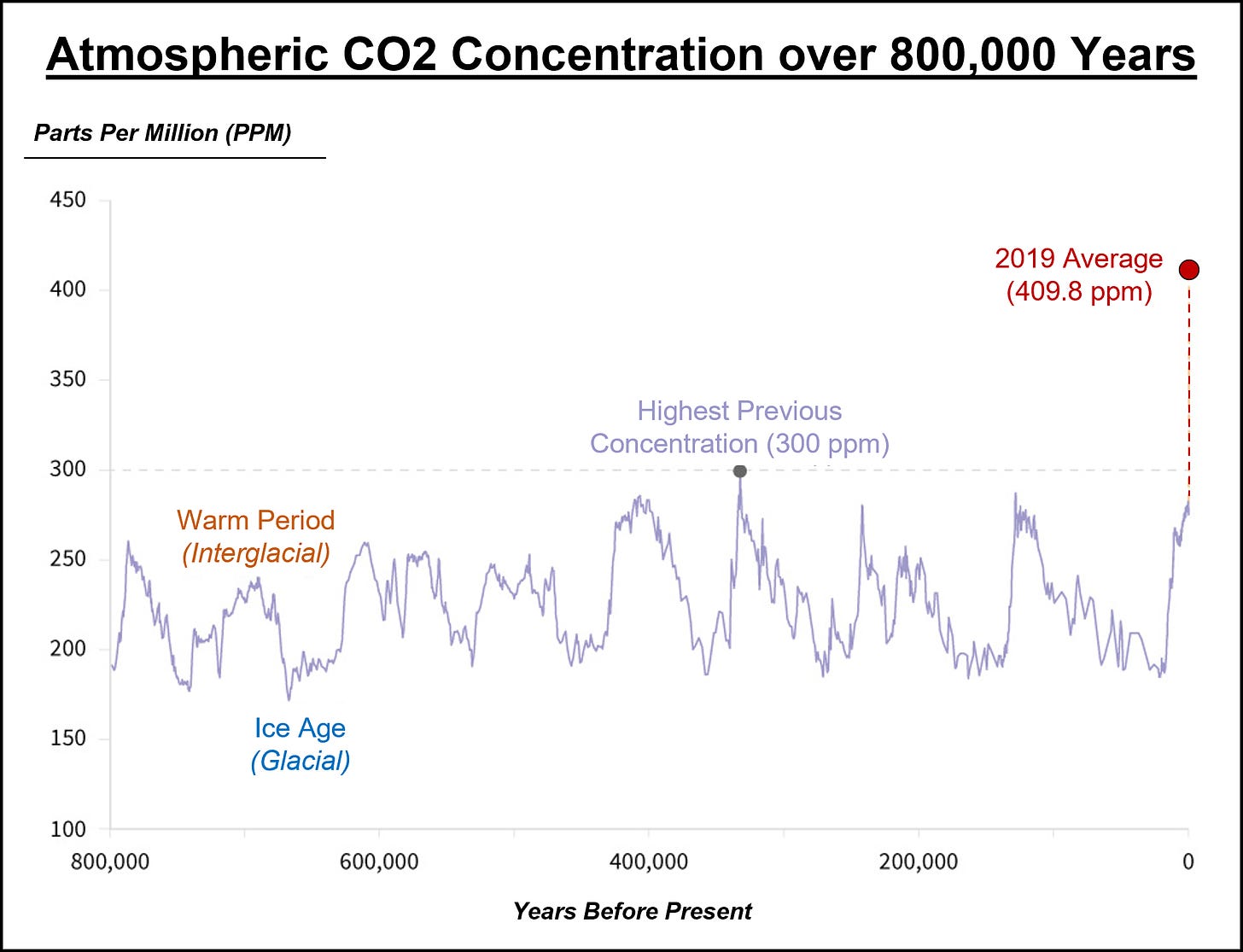

On a longer timeframe, the recent rise in CO2 concentration is even more startling.

To recap, atmospheric CO2 concentration has:

Increased by ~47% since before the Industrial Age.

Increased by ~11% since the year 2000.

.

At this point, you may be asking - why should I care about CO2 concentration? Or maybe – what does any of this have to do with NETs?

Both are fair questions.

A few weeks ago I stumbled on this article from Yale’s School of the Environment. One sentence caught my attention:

“Negative emissions technologies solve the root cause of climate change — too much CO2 in the atmosphere.”

Well, who doesn’t want to solve the root cause of climate change?!

The Holy Grail: Negative Emissions 👼

I like Yale’s explanation of climate change; it’s simple and easy to understand.

The rising concentration of CO2 in our atmosphere (aka “too much CO2”) is the main underlying factor driving changes in the earth’s climate.

That explanation also helps to clarify why countries globally are making increasingly assertive emission reduction pledges. One such example is the pursuit of Net-Zero by 2050, which was the cornerstone of the coveted 2015 Paris Agreement.

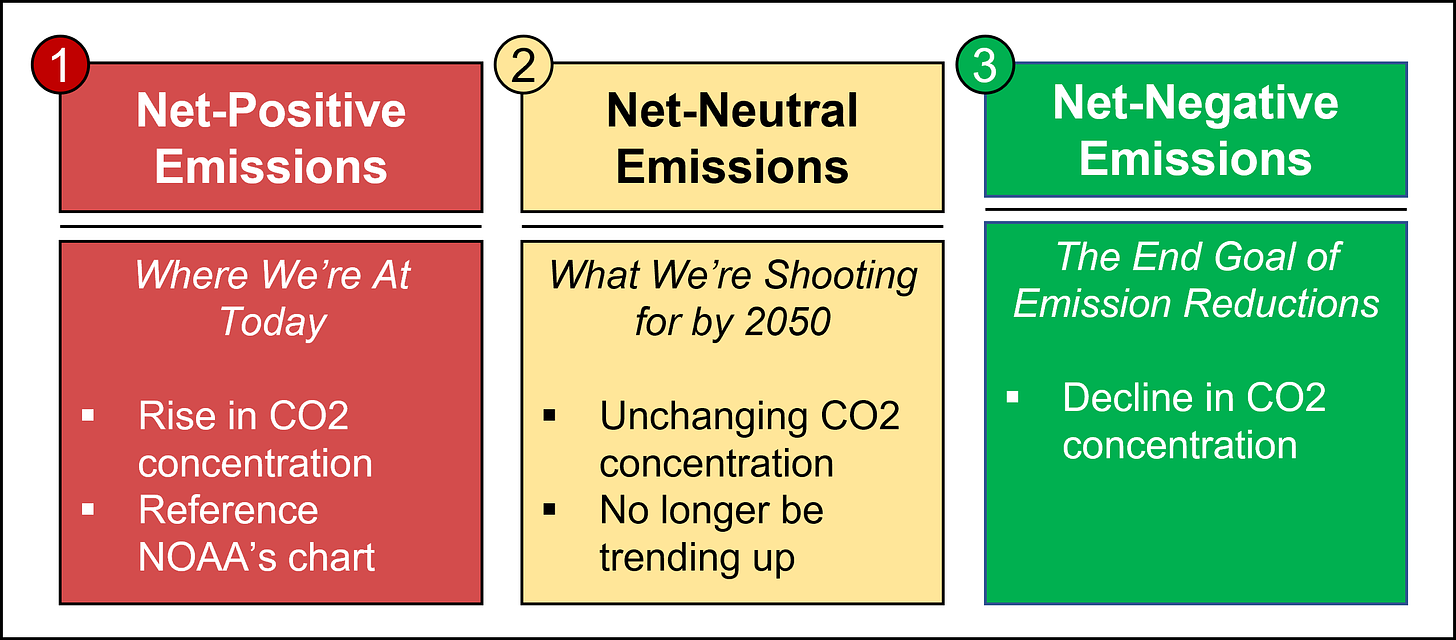

Interestingly, Net-Zero isn’t really our end goal though. Instead, it’s a stepping stone towards Net-Negative emissions further down the road.

Picture three states of the world, each with a unique emissions scenario:

The speed at which we move from #1 (where we’re today) to #3 (our end goal) will contribute to the severity and repercussions of global climate change.

To facilitate that transition, humans have two levers on which to pull:

Less Positive Emissions: Reducing future emissions, by decarbonizing our energy system and other industries.

More Negative Emissions: Increasing the capacity of carbon sinks to capture and store CO2 directly from the atmosphere.

.

Lever #2 brings us full circle to the role of NETs.

The potential for Negative Emission Technologies to remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere, on a scale large enough to move the needle, is an exciting prospect.

NETs present an opportunity to target the root cause of climate change (CO2 concentration) and accelerate the global pursuit of Net-Zero.

Our Drive to Decarbonize 🚬

Despite the litany of carbon-related promises and policies laid out globally, reducing our emissions will be no easy task.

The U.S. will undoubtedly serve as a great example of that reality. Particularly in light of a recent announcement by President Biden.

By 2030, the U.S. aims to reduce GHG emissions by ~50%, relative to 2005.

The emissions reductions that Biden is targeting would be unprecedented. As in, never happened before.

The good news: American GHG emission peaked in the mid-2000s, so at least the U.S. has a 15-year head start in meeting Biden’s objective.

The bad news: Biden’s plan implies that in the coming decade, the U.S. will decarbonize at a rate four times faster than over the last 15 years.

.

No easy feat, indeed.

How to Stop Our Ship from Sinking 🚢

To help explain the rationale behind NETs, I’ll use an analogy: picture a ship that’s been out at sea for many years.

Over time, that ship sprung a few leaks. And now, those leaks are letting water seep into the ship’s hull. Initially, there were no immediate consequences to the rising water level. But over time, the ship took on more and more water.

Now, it’s at risk of sinking.

To solve the problem, the ship’s crew has two options:

Plug the holes: The immediate issue is that, as more water enters the ship, the risk of sinking continues to grow. Repairing the holes would stop the problem from getting worse. But there would still be water in the ship.

Bail out the water: The root cause of the ship’s problem is that it’s full of water. This creates a risk that, even when the holes are plugged, the ship may still sink. Bailing out the water would address the ship’s main problem.

.

Neither solution would work well in isolation. In the long term, the ship’s crew should focus on both plugging the holes and bailing out the water.

That ship is the earth’s atmosphere. The water is our carbon dioxide.

Through our decarbonization efforts, we’re working to plug the holes. And hopefully, by 2050, those holes will be plugged. But even then, there will still be too much water in the boat.

So, we may also want to consider grabbing a NET-shaped bucket.

The Many Different Paths to Zero 🚶

There is no single path to achieve Net-Zero by 2050. Instead, there are many. Each path will employ a different combination of less positive emissions, and more negative emissions.

But the longer we procrastinate on reducing future emissions, the more critical NETs will be to manage the quantity of carbon in our atmosphere. This infographic, published by Glen Peters, does a great job of highlighting that reality.

The longer it takes to reduce our positive emissions (brown shading), the more important negative emissions will be (green shading).

Simply put, the slower the pace of emission reductions, the more reliant we will become on NETs to achieve our emission goals.

A Closing Note on NETs

In 2019, the IPCC published a report which drove home the importance of NETs.The report laid out what needs to be done to limit global warming to 1.5⁰C.

In every single scenario, NETs played a critical role.

Unfortunately, it would be misleading to present NETs as a silver bullet for climate change mitigation. The technology remains nascent and is still constrained by cost.

But so too was the case for renewable energy a decade ago. Today, thanks to innovation and policy support, that is no longer the case. The same could very well be true of the NET industry in the decades to come.

And ultimately, should the world continue to decarbonize at a snail’s pace, we will have little choice but to deploy NETs at scale in order to achieve our decarbonization objectives.

Net-Zero 2050, here we come?

Not to be confused with NFTs (non-fungible tokens) which I know nothing about.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)