Year in Review: 2022

the Plug #31 | A Reminder that Fossil Fuels Remain King 👑

“All good things arrive unto them that wait - and don’t die in the meantime.”

— Mark Twain (on decarbonization)

In 2022, policy and geopolitics-related catalysts had an outsized impact on our global energy system.

Quite fortuitously for me, earlier this year, I moved to DC to start a new job as an energy policy consultant. Two weeks after finding my new desk, on February 24th, Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine. The Russia-Ukraine conflict served as rocket fuel, accelerating the dislocation in fossil energy markets that pre-dated the war.

Ten months into the job, my biggest surprise has been the extent of the disconnect between investors in New York and operators in the Permian and the Marcellus relative to policymakers in Washington.

I believe this disconnect can be explained, in part, by the fact policy and geopolitics have largely been an afterthought in energy markets for decades. The world has long remained relatively peaceful. The US’s role in that world has been clearly defined and largely predictable. Amid that backdrop, which I believe can loosely be traced back to the falling of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the role of policymakers in the global economy has been relatively muted.

However, I see the confluence of notable events in 2022 as evidence that policy and geopolitics will play an increasingly significant role in our global energy system in the years to come. For example, the pursuit of decarbonization will exacerbate geopolitical friction in at least two ways:

Through the necessary formation of new supply chains for materials critical to a clean energy economy (i.e., cobalt, lithium, etc.)

Via the local supply-demand mismatches that will emerge as countries seek to displace fossil energy (i.e., EU circa 2022).

This past year, energy security (and the lack thereof) began to matter again. I understand the concept of energy security as the combination of affordability, reliability, and stability of energy supply.

As energy insecurity began to seep into the world economy, it manifested in energy policy decisions globally. The resurrection by Western governments of long-decreased energy policy constructs, including windfall profit taxes, price caps, and trade embargoes, is a symptom of this dynamic.

Fossil Energy Supply Chains are 🔑 to Energy Security

I believe it’s important to remember the extent to which the global economy remains dependent on fossil energy supply. In 2021, 83% of the primary energy consumption globally was attributable to coal, oil, and natural gas. As a result, control over the supply chains that deliver us fossil energy supply remains the key to national energy security. That reality is geographically agnostic and equally relevant for both developed and emerging economies.

Global underinvestment in upstream fossil energy production capacity and the critical infrastructure that underpins it, which began in earnest in 2015, has played a key role in recent geopolitical developments. In part because the current shortage of fossil energy molecules has increased the relative bargaining power of countries with control over fossil energy supply chains.

In 2023, and until we see a resurgence in investment in upstream production capacity and critical infrastructure, I expect the countries that control fossil energy supply chains will continue to be surprisingly assertive in their pursuit of domestic and foreign policy priorities.

This dynamic was apparent in Putin’s rationale back in February. The ongoing conflict exemplifies the perception of increased leverage held by countries that control fossil energy supply chains amid the prevailing supply shortage. Until there is a resurgence in upstream fossil energy investment, this power dynamic will persist.

I wrote about my energy-related views on the Russia-Ukraine conflict extensively four days after Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine. You can read it below. 👇

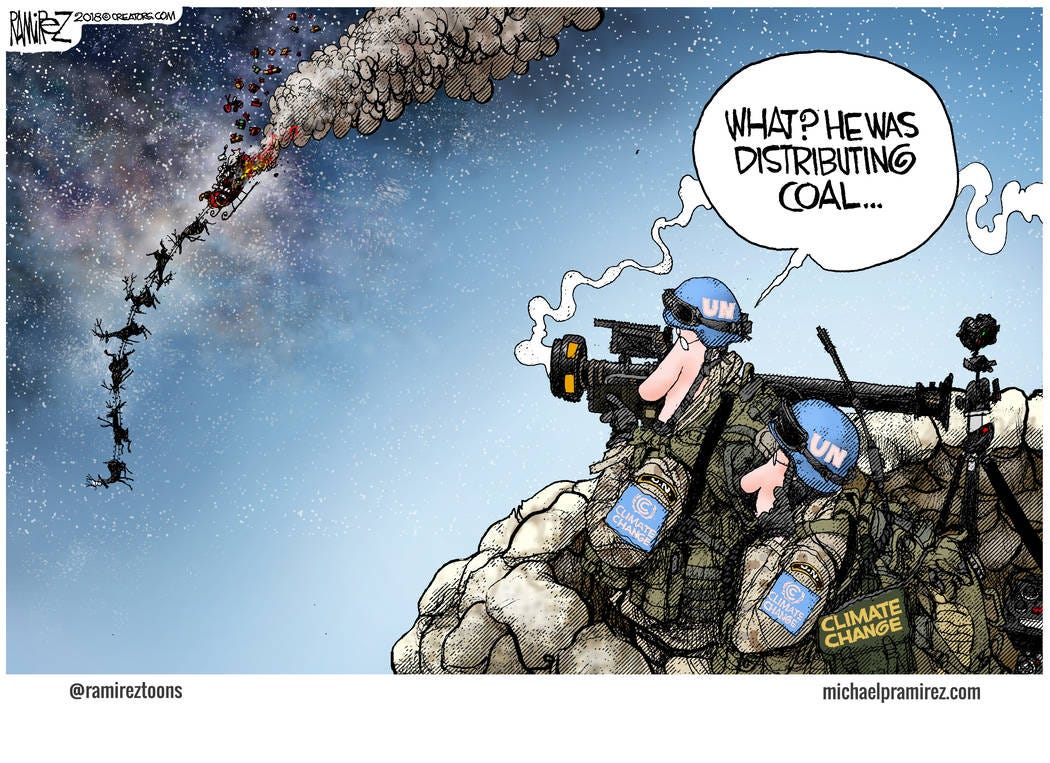

After spending the last year studying Western energy policy decisions, it seems abundantly clear that many politicians have yet to come to terms with the fact that fossil energy supply remains the key to energy security. Alternatively, for the recently enlightened, the momentum behind past energy policy decisions has thus far overwhelmed a pivot toward pragmatism.

That realization will undoubtedly dawn eventually. In the meantime, the question remains, how much more pain in energy markets will be required to elicit a rational response from policymakers?

Some Optional Longer Reading

For those interested in the long-form version of my year-end soliloquy, I wrote recently about my expectations for the coming year on the geopolitics of the energy transition. Specifically, I attempt to explain why I think the energy policy decisions in Turkey, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and Germany will be well worth watching this coming year.

You can read and download it at the link below. 👇

(It is pretty long and so I won’t blame you for scrolling past it.)

Happy Holidays & Thanks for Still Being Here

Unfortunately, this past year, my newsletter publishing cadence slowed to a crawl as the competing priorities of work and life took the wheel. While I hope to find more time for long-form writing in 2023, I’d encourage you to check out my Twitter @thePlugWeekly for a more regular stream of my consciousness.

Happy new year to those that celebrate. Here’s to hoping that the green shoots of energy policy pragmatism that began to appear in 2022 take root in 2023!

Great to see you back writing - sharing thought provoking ideas in an easy to absorb manner. May 2023 be as eventful as you want it to be!