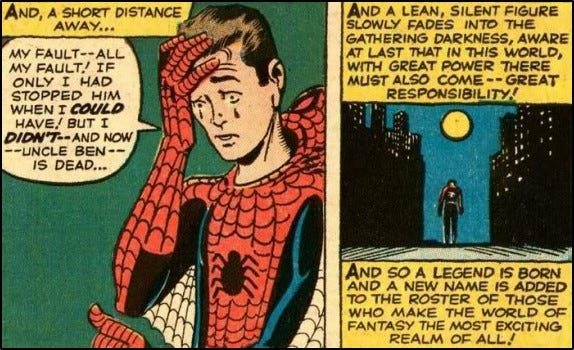

“And a lean, silent figure slowly fades into the gathering darkness, aware at last that in this world with great power there must also come -- great responsibility!” – Spiderman

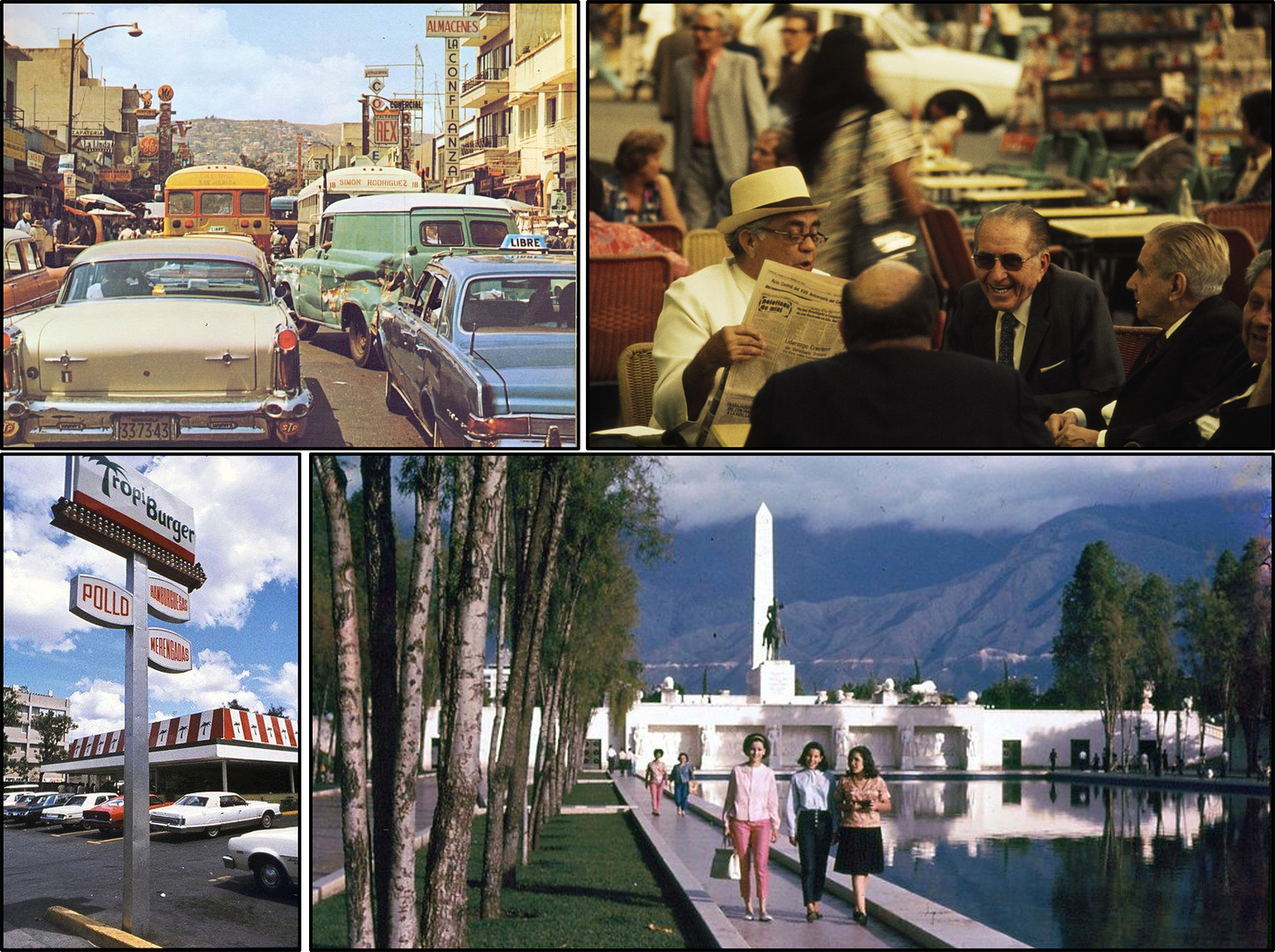

If there were ever a perfect moment to be living in Venezuela, I believe it would have been in the late 1970s.

At the time, in the country’s capital city of Caracas, the city’s streets hustled and bustled with Chrysler New Yorkers and Plymouth Valiants. The storefronts lining those streets were filled with great restaurants, serving everything from pabellón to pastries. And, scattered throughout the capital were tourists, who were flocking into the country with hopes of catching a glimpse into the South American joie de vivre.

For some time, Air France offered a flight directly from Paris to Caracas on the now-deceased Concorde airplane. Air France’s byline advertising the trip from France to Venezuela read, “The easiest 6 hours you’ve ever flown.”

The cherry on top of Venezuela’s banana sundae was the influx of immigrants coming into the country from Europe, Colombia, and elsewhere in search of a better life.

Unfortunately, I’ve struggled to find much in the way of reliable eye-witness accounts of what life in Venezuela resembled in the late 1970s. So, instead, I’ve been reliant on old photos and videos from that time.

Undoubtedly, for Venezuelans living inside the country during the late 1970s, life was not without challenges and hardship. But, from the outside looking in, life in Caracas didn’t necessarily look all that different from life in other major cities.

Which makes sense. Because in the late 1970s, Venezuela had the highest GDP-per-capita of any South American country.

Which may leave you wondering, how the hell is that possible?

Good question.

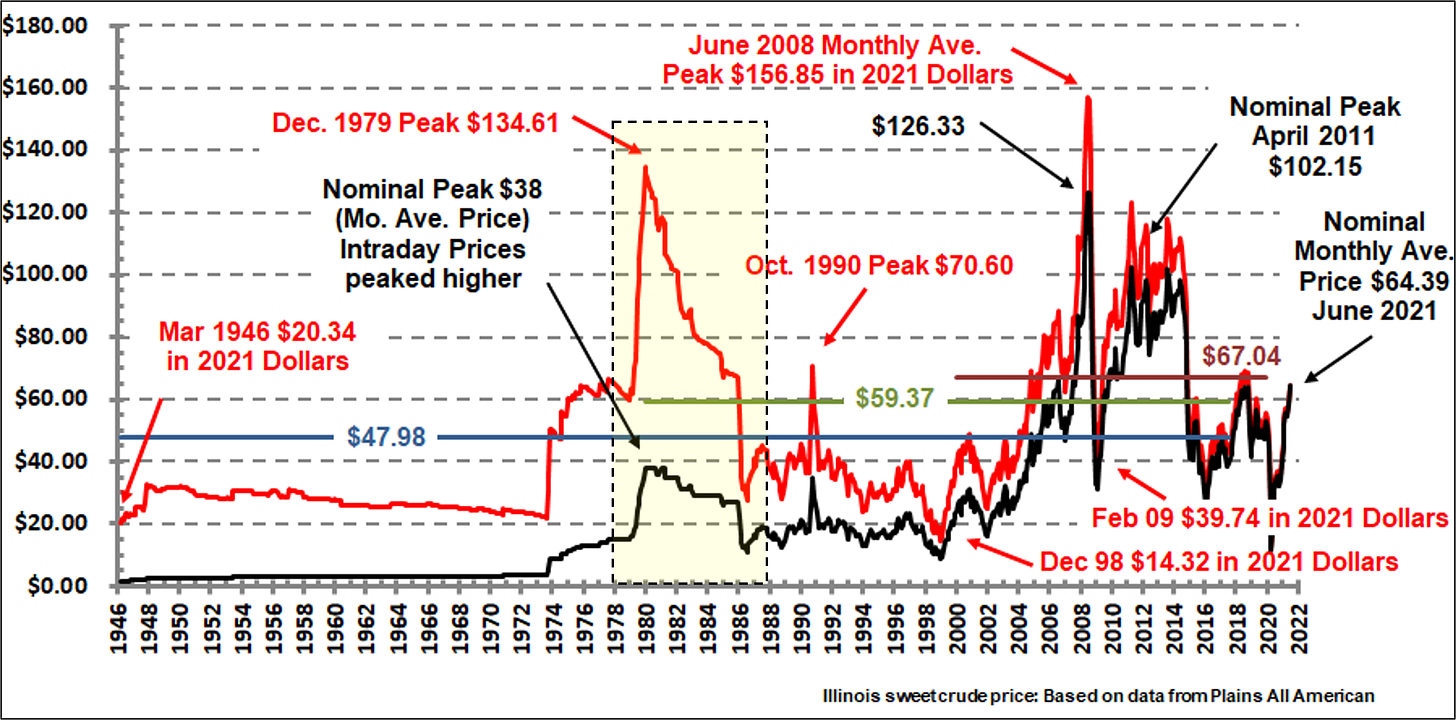

Venezuela’s good fortune was in no small part thanks to a crisis that was unfolding halfway across the world. The Islamic Revolution broke out in Iran in 1978, catapulting oil prices to new all-time highs. Middle Eastern turmoil has always been a reliable harbinger of crude oil bull markets.

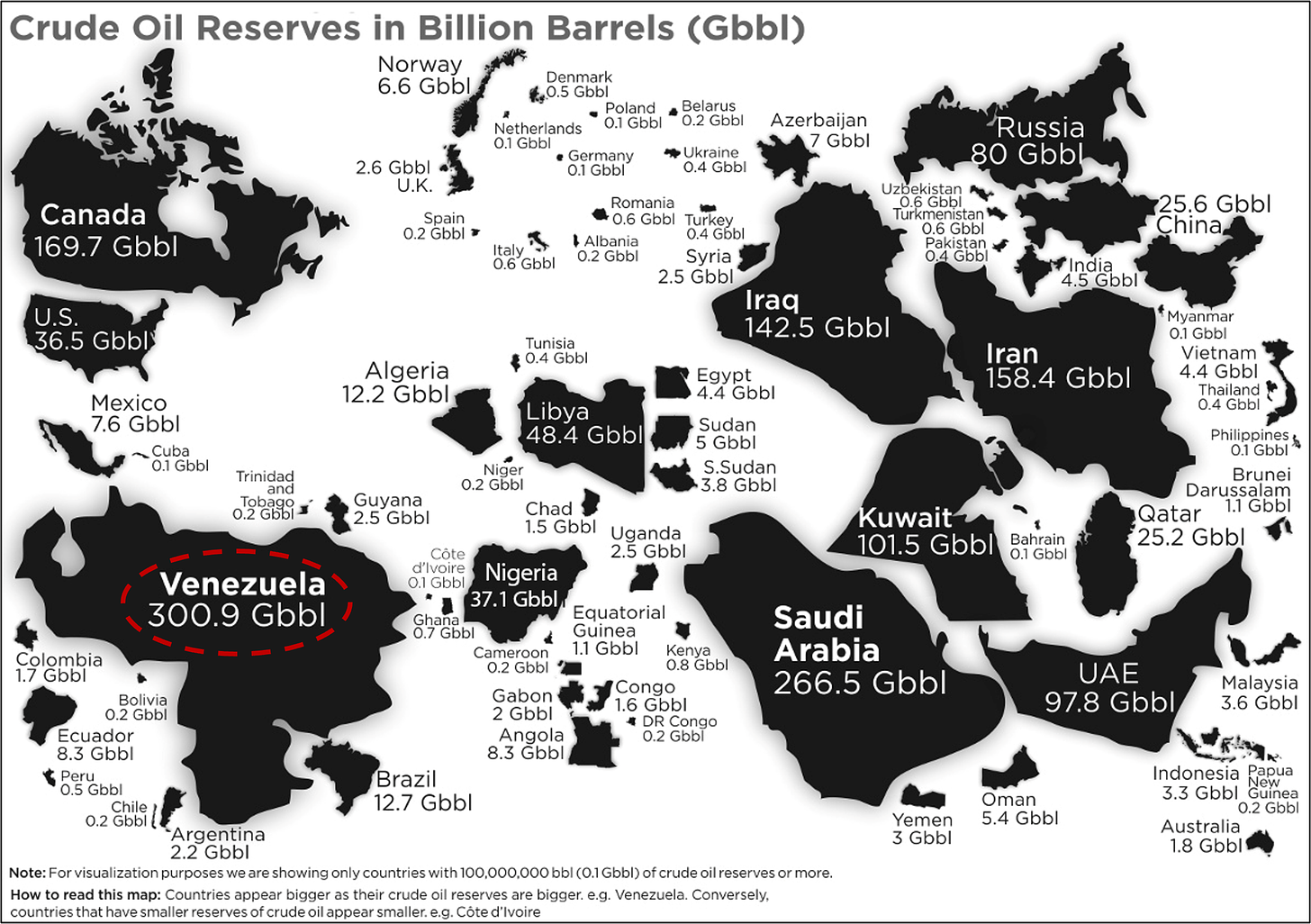

Rising oil prices generated a profit windfall for the state and its citizens. Because, still to this day, Venezuela has the largest proven crude oil deposits of any country globally.

It’s probably also worth mentioning that by the late 1970s, the seeds of Democracy had been growing roots across Venezuela for nearly two decades.

Following a public uprising in 1958, the country’s citizens had seized power from hardline dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez. The late autocracy gave way to the country’s first democratic experiment, whereby two political parties were established to share power.

That system, filled with checks and balances on power, held up for many years after that.

Venezuela’s new leadership were scholars of history and knew that oil markets experience frequent bouts of volatility. They internalized the fact that, in many ways, oil prices fluctuate like yoyos. So, after the former dictator’s fall, the country’s political elite prepared diligently for impending uncertainty.

Diversifying the country’s economy was a critical strategic priority for the new administration. They dutifully spread the profits reaped from domestic oil production across all sectors of Venezuela’s domestic economy. The Venezuelans also exercised incredible restraint and resisted the temptation to overleverage themselves to pursue short-term oil profits.

The government’s pièce de résistance was the establishment of a sovereign wealth fund through which the country and its people could capitalize on international investment opportunities. Thereby further diversifying Venezuelan’s wealth internationally.

Lastly, the government invested heavily in robust healthcare, transportation, and communications infrastructure to increase all Venezuelans’ quality of life.

The Venezuelan people lived happily ever after.

Just kidding… Forget about everything I just said.

Except for the part about life being pretty good for Venezuelans in the late 1970s. And the part about Iran’s revolution. Those parts, to the best of my knowledge, are accurate.

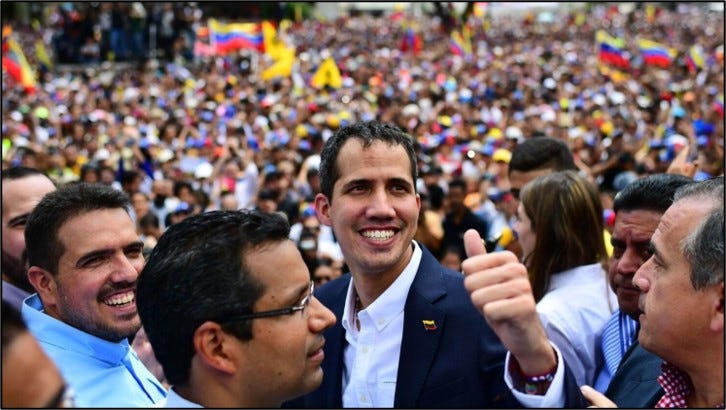

And that last photo?

Well, for those paying attention, that’s Juan Guiado. He’s currently the leader of Venezuela’s opposition party. Unfortunately, he’s not relevant to our story today. Nevertheless, I wanted to make note of his bravery and resilience.

☝️1st Principles: Natural Resources & Geopolitics

Two weeks ago, I revisited the role of crude oil in World War II (WWII).

More specifically, I ran through a historical example whereby a country (the United States) leveraged its domestic resource supply (crude oil) to gain international geopolitical influence (to win WWII). If you haven’t yet read it, I’d encourage you to go back and, at the very least, give it a skim.

It sets the stage for my takeaways in this piece.

Initially, I thought it was safe to say that I’d established a first principle on the relationship between natural resources and geopolitics! I was pretty content for a day or so — whoop de doo.

Upon further reflection, I realized that my new theory contained holes so large that you could realistically fly a Concorde plane through them. My “first principle” was no better than a piece of Swiss cheese.

That realization is why I’m now taking a stroll through Venezuela. Because Venezuelan soil boasts a practically limitless supply of crude oil.

Under our newly established and overly simplistic theory, Venezuela should have capitalized on its domestic resource supply to elevate itself on the world stage.

And yet, today, the country finds itself in chaos and disarray.

Sadly, somewhere along the line, Venezuela fell victim to the resource curse. That’s what we’ll be discussing today, alongside a brief history of Venezuelan politics.

My hope is that we’ll conclude this journey by adding a few addendums to our shaky first principle.

Buckle up.

🏛️The Crumbling Foundation of Democracy

As our fictitious Venezuelan politicians wisely predicted, what goes up must eventually come down.

Beginning in 1980, as turmoil subsided within the Imperial State of Iran, oil prices started to bust. Slowly at first. And then, in 1986, all at once. The downturn in oil prices stoked unrest in Venezuela, whose leaders likely had their foresight clouded by the potential spoils of a prolonged black gold bull run.

The ensuing oil price downturn, stretching from 1980 through 1986, led to an economic crisis within Venezuela.

Inflation began to rise uncontrollably. The Bolivar started to weaken. And, suddenly, the quality of life in Venezuela was taking a turn for the worst.

Every competent dictator knows that in crisis comes opportunity. But it’s impossible to pinpoint exactly when exactly Hugo Chávez began to smell blood in the water.

However, in 1992, Chávez had finally built up the courage to pounce.

Unfortunately for him and his supporters, the coup failed. But, for some reason, his captors did something puzzling. Fresh off his attempt to overthrow the existing administration, Chavez was granted the opportunity to lead a nationally televised address. He seized on his waning moment in the limelight to declare:

“We have failed, for now.”

Six years later, in 1998, Chávez was back and more popular than ever. He won that year’s election in a landslide.

Now, I won’t bore you with too much more detail on Venezuelan politics. But there is one more turn in this story that’s worth mentioning.

In the decades that followed Chávez’s election victory, Venezuela’s political scene was, let’s say, tumultuous. Eventually, in 2013, as he lay on his deathbed, Chávez handpicked Nicolás Maduro as his successor. To this day, Maduro continues to reign over Venezuela with an iron fist.

The country, which resembled many of North America’s more developed cities in the 1970s, now looked more like this on some days over the past few years:

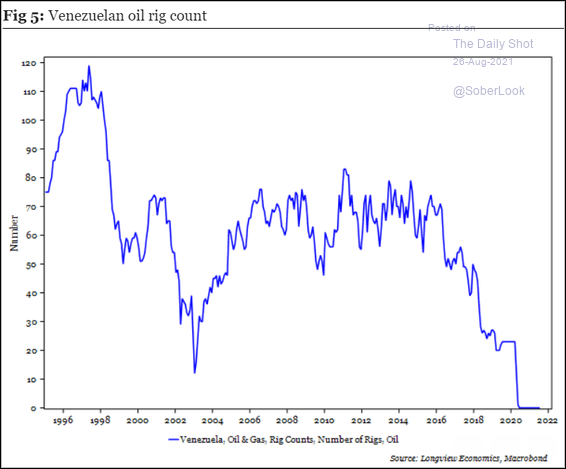

And the progress of building up Venezuela’s domestic oil industry (as depicted by the number of oil rigs running inside the country) now looks like this:

Notably, Venezuela didn’t take a single piece of the advice I laid out in my introduction.

It failed to diversify the economy. Instead, the counted leaned heavily on oil production at the expense of its manufacturing and service sectors

It did not invest in infrastructure, neglecting to establish the base necessities for long-term economic growth and prosperity

It took on way too much debt, specifically on the balance sheet of its national oil company, PDVSA

It never established a Sovereign wealth fund, unlike other global oil producers like Norway and Saudi Arabia

.

These outcomes are all classic symptoms of the aforementioned resource curse.

Now, there is one specific dynamic within the resource curse that I want to burrow down into. Because remember, we’re trying to establish a robust first principle here.

🌪️A Misalignment of Incentives

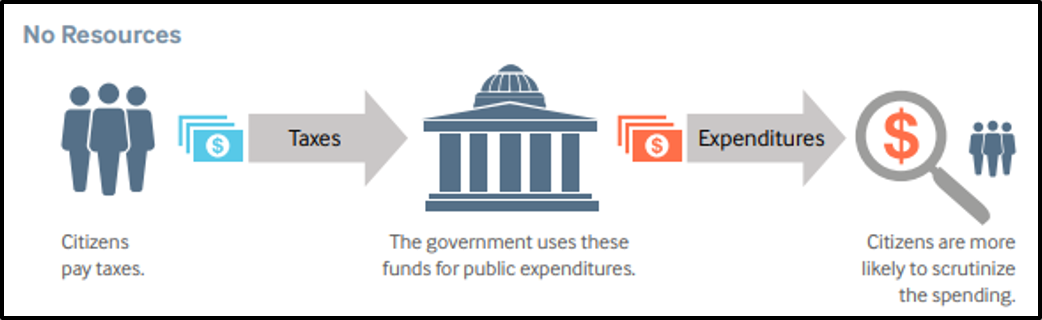

I’ve heard it said that there are two certainties in life: death and taxes. But, for countries with an abundance of natural resources, the certainty of taxes becomes a bit more ambiguous.

In the absence of resources, it is citizens who pay the taxes required to keep the government running. As a result, citizens have a certain degree of influence because their tax dollars are necessary for the government’s survival. This “agreement” creates an incentive for the government to keep its population content.

The citizen body also has some visibility into the amount of taxes they’re paying, which reduces the potential for information asymmetry between citizens and their government.

Without natural resources, the relationship between a government and its citizens is relatively simple.

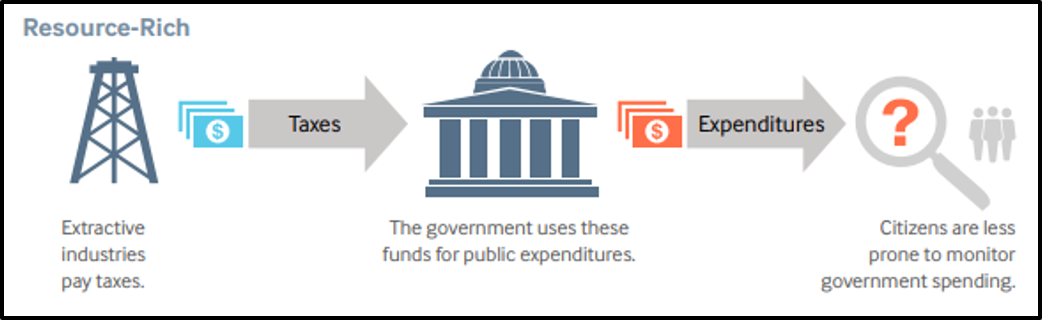

The discovery of resources changes this ball game entirely.

No longer is the government reliant on its citizens for tax revenue. Because, instead, there’s enough tax revenue being generated by the production of natural resources.

And, because the taxes paid by citizens are no longer the government’s primary source of income, it becomes increasingly challenging for the citizen body to know just how much tax revenue their government is pulling in.

Without robust government institutions, this change in dynamic has the potential to reduce (or even eliminate) the citizen body’s influence.

The power balance shifts towards those in charge of the government.

In Venezuela, Chávez and Maduro took advantage of this dynamic for enormous personal gain. All at the expense of the Venezuelan population.

At the time of Chávez’s death in 2013, his net worth was estimated to be over US$1 billion. Although, importantly, that dubious figure should be taken with a handful of salt. It could be a lot more, and, in theory, it could also be less.

My money is on “more.”

Today, press freedom in Venezuela is at or near an all-time low. Its economy, over-reliant on oil production, is in tatters. Its currency, the Bolivar, continues to spiral upwards as inflation runs rampant. And some of Venezuela’s best and brightest minds have fled the country in search of more lucrative job opportunities.

Sadly, the remaining Venezuelan population is now left holding the bag.

I’m reminded of a scene in Happy Gilmore where a menacing anti-Shooter McGavin spectator is wearing a t-shirt that reads, “Guns don’t kill people. I do.” I believe it bears an essential reminder in the context of Venezuela’s downward spiral.

It wasn’t crude oil that decimated Venezuelan prosperity. Instead, it was the people in power.

⚠️An Important Sidebar

I want to caveat this piece with an important reminder.

I would be remiss not to take this opportunity to draw attention to the humanitarian crisis that continues to unfold in Venezuela. While media coverage of Venezuelan unrest may have died down over the past year, I understand that the situation on the ground remains as dire as ever — particularly given the challenges created by the COVID pandemic.

While I may use comedic relief in my writing to try and make the otherwise dull topic of energy somewhat interesting, I don’t intend to poke fun at the tumult that continues to take place in Venezuela today.

I can’t imagine the hardship and misery that has become commonplace inside Venezuela.

The site linked here lists 47 projects in Venezuela that NGOs and non-profit organizations are currently running. The various initiatives focus on childhood education, food insecurity, hunger and malnutrition, water sanitation, among other noble and essential causes.

While the reach of this newsletter may be small, it is not non-existent.

If you’ve derived any value whatsoever from this newsletter (which I’ll continue publishing for free), please consider showing your appreciation by donating to any of the charities I linked above.

💡Wrapping Up

Without further ado, let’s revisit our trusty first principle.

What can be learned from Venezuela in the context of the strategic geopolitical benefits that a country can reap from its natural resource supply?

There are, at least, a few notable takeaways:

A Stable Power Structure is Necessary: By nature, natural resource extraction projects are “long cycle.” Within the oil industry, for example, it takes decades to discover, extract, and process resources to bring them to market. Not to mention the infrastructure that needs to be established and maintained along the way. To derive long-term benefits from natural resources, there needs to be a consistent and long-term government focus on doing so. Notably, stability doesn’t necessitate Democracy, as evidenced by Saudi Arabia’s long-standing monarchy.

Economic Diversification is Key: Extractive industries and the commodities they produce will always be cyclical in nature. When times are good, and prices are high, it can be tempting to double down on the industry responsible for generating most of a country’s economic growth. But, when it inevitably rains, you’ll be happy to have invested not only in sunscreen and swim shorts but also in umbrellas and rain jackets.

Clear Priorities are Critical: Lastly, for a country to leverage its natural resources for geopolitical influence, it needs to want it. Resources (time, attention, capital, and workforce) spent galivanting abroad come at the expense of resources spent on other priorities. A dollar spent on one thing is a dollar not spent on another. There will always be an opportunity cost to pursuing geopolitical influence. The question is whether or not that opportunity cost is worth the expenditure.

.

From our newly laid theoretical foundation, I believe there’s an exciting extrapolation to be made about the future of global geopolitics. Specifically, surrounding the relationship between the world’s two great superpowers: the United States and China.

But I’ll leave that extrapolation for another day.

As I opened with Spiderman, it feels fitting to close on a similar note.

Sadly, I don’t believe either Chávez or Maduro was familiar with Peter Parker’s adventures. Or, at the very least, they failed to take note of the maxim embedded within Spiderman’s origin story.

“That in this world, with great power [stemming from an abundance of domestic natural resources] there must also come -- great responsibility [for the well-being of a country’s citizens]!”

The opening took me into the smells and colors of a South American capital. And enjoyed how much I learnt in this edition. Paired with last episode on Crude Oil's role in WWII and fossil fuel geopolitics since, I'm really enjoying how much history I'm learning from the Plug!

this was a super engaging piece, loved it Adam