A warm welcome to our news subscribers. If you haven’t yet subscribed, the link below will help solve that problem. 👇

As far back as records exist, naturally occurring forest fires have scorched North America’s landscapes. And yet, every summer, our inability to contain increasingly destructive forest fires is blamed primarily on climate change.

Thus far, this summer has been no different.

Since the 1980s, North American forest fires have steadily grown more destructive. And climate change has certainly been a contributing factor. But we aren’t powerless to limit the devastation wrought by forest fires.

Today, we’re going to look at:

The largest documented forest fire in American history 🔥

The changing nature of North American forest fires 🌲

What role climate change plays in exacerbating fire seasons 🌡️

What’s in our control, and why proactivity is important 👨🚒

If you’re enjoying the Plug, I’d really appreciate your help in growing our distribution. Please consider sharing it with friends and coworkers. 🙂

A Preamble on “The Big Burn” 🔥

I recently stumbled upon an article recounting what is believed to be the biggest American wildfire in recorded history. It took place in 1910.

Here is a high-level summary of the fire’s impact:

It burnt ~3 million acres of forests.

At its peak, the flames burned over an area the size of Connecticut.

At least 87 people were killed, of which 78 were firefighters.

The bravery of firefighters, both then and now, shouldn’t go unmentioned.

Every year, firefighters put their lives on the line to try and limit the impact of forest fires on the human population. From my perspective, that’s as noble a cause as any.

Updating Our Response to Forest Fires

In the decades following The Big Burn, a warlike approach was developed to tame forest fires. That strategic approach persists to this day.

We employ proactive tactics, including the inducement of pre-burns, and the digging of trenches. Through the use of manpower and heavy equipment, we bend the natural landscape to our will, in order to disrupt fuel continuity.

And reactively, firefighters battle flames from the ground, while helicopters and planes suppress fires from the air. Using water and fire retardants, the objective is to choke out the fire’s oxygen supply in order to slow it down.

These tactics were developed in response to growing pressure on government officials and fire departments to minimize the impact of forest fires on our societies. But as early as the 1970s, scientists understood that North America’s ecosystem depends on periodic fires to remove debris and eliminate ailing vegetation.

In spite of that understanding, we continue to wrestle forest fires into submission wherever they appear. And the repercussions from those decisions may be catching up to us.

Fast Forward to Present Day

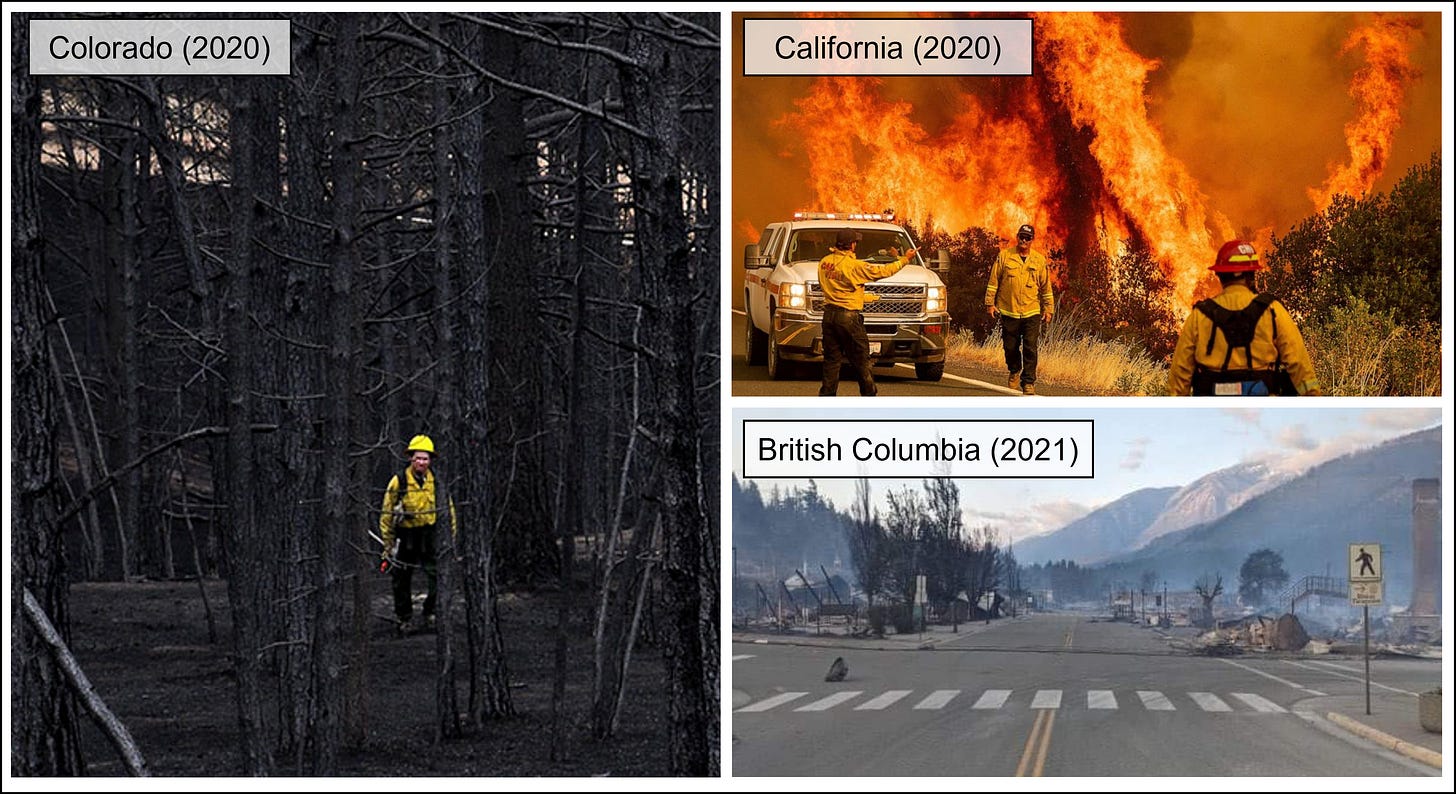

The photos from 1910 reminded me of the recent devastation in Lytton, B.C., and of other wildfires on the West Coast of North America.

During The Big Burn of 1910, climate change wasn’t yet on our radar.

And given the primacy of early 1900s society, it’s hard to argue that energy consumption, CO2 emissions or climate change were to blame for the fire.

My point is that the presence of naturally occurring forest fires in North America undoubtedly predated human influence on the planet.

Quantifying the Evolution of Forest Fires 🌲

The U.S.-based National Interagency Fire Center provides two data sets on American forest fires annually, starting in 1983:

Frequency: The number of wildfires.

Severity: The acreage burned by wildfires.

.

There are other notable factors. Loss of human and animal life, and the destruction of private property, are three other important considerations.

But today, let’s focus only on two factors.

The Frequency of Forest Fire

Before looking at the chart below, please venture a guess as to whether American forest fires are more or less frequent today than they were 40 years ago?

If you guessed neither, then chalk up ten points to your relevant team at Hogwarts.

We should rest assured that over the past four decades, wildfires have not markedly increased in frequency. In fact, in only two of the last ten years has the number of wildfires exceeded the 38-year average.

But that reality isn’t sufficiently newsworthy for media organizations, and so it isn’t often discussed.

The Intensity of Forest Fires

Shifting now to the intensity of U.S. forest fires.

I’ll pose a similar question; do you think the acreage burned by U.S. forest fires annually has increased or decreased since the 1980s?

Unlike with frequency, four decades of data show a clear trend in the intensity of American forest fires: increasing over time.

So on one hand, the number of forest fires in the U.S. isn’t increasing. But on the other hand, the relatively constant number of forest fires are burning increasingly more land.

Why is that?

Takeaways From This Contradiction

Think back to the forestry management and firefighting practices we developed through the 1900s.

I can’t believe I’m saying this. But some (definitely not all) of the high-level points made by former President Trump in late 2020, calling out the mismanagement of California’s forests as a factor in the State’s forest fires, are valid.

Instead of effectively managing forest fires, by making short-sighted decisions we may have just been kicking an increasingly flammable can down the road.

Longer-dated records on North American forest fires would help to answer that question. Unfortunately, to my knowledge, data from pre-1983 isn’t publicly available.

Forest Fires & Climate Change 🌡️

Too often, media organizations highlight an overly simplistic relationship between hotter temperatures and worsening forest fires. But that perspective doesn’t do justice to the complexity of climate science or forest fires.

There are lots of noteworthy factors to consider in the relationship between our changing climate and forest fires.

Temperature: Is it getting increasingly warmer during the summer? Is the summer lasting longer? Is the average yearly temperature increasing?

Precipitation: What’s going on with precipitation patterns? Is it raining or snowing less frequently or less intensely?

Plants: Have changes in our climate affected our flora and fauna? If so, what are the implications for forest fires?

.

While oversimplification may be the bread and butter of media organizations, it falls short in addressing complicated challenges like forest fires and climate change.

Today, let’s first look at the evolution of annual extreme warm temperatures in the continental U.S. from 1900 through 2017.

It turns out that in the Continental U.S., extreme warm annual temperatures peaked during the period of 1920 through 1950. And in many areas within the U.S., the highest temperature recorded annually decreased by several degrees in the period of 1986 through 2016, as compared to the period of 1901 through 1960.

Let’s look at the progression of annual extreme cold temperatures in the U.S.

Unlike extreme warm temperatures, extreme cold temperatures in the U.S. have shown an increasing trend. And record cold annual temperatures in 1986 through 2016 were generally less cold than in the period of 1901 through 1960.

So, Is It Getting Warmer?

From the perspective of extreme temperatures, weather in the continental U.S. has become milder – with less variability between the extreme lows and the extreme highs each year.

The record cold temperatures each year are becoming less cold, while the record warm temperatures are not at their record peak. So, indirectly from those charts, you could conclude that temperatures are in fact getting warmer.

But really, that one data set tells us that climate in the continental U.S. is getting less cold, and milder.

That’s not to say that the average temperature in the U.S. isn’t increasing. According to the EPA, the temperature in the Continental U.S. has warmed dramatically since 1900. Instead, it’s to highlight that climate science is more complicated than we give it credit for.

The impact of changes in North America’s climate has undisputedly influenced forest fires.

But calling out a black-and-white relationship between forest fires and warming temperatures requires nuance. And recognition of our weather systems’ complexity.

Mitigating the Impact of Forest Fires 👨🚒

Let’s look at some of the things in our control when it comes to mitigating the damage from forest fires.

Forestry Management: The importance of managing the kindling that enables increasingly severe forest fires can’t be overstated. To mitigate the near-term impact of forest fires while maintaining a longer-term perspective, proactivity around forestry management is key.

Fire Fighting: As our changing climate exacerbates the intensity of forest fires, increasing funding allocated to firefighters will allow them to do their jobs to the fullest of their ability. We need to be able to respond effectively to the inevitability of forest fires now and in the future.

Addressing the Cause: Let’s continue to look at the root cause of forest fires, and address them. Over 90% of forest fires are started by human activity, and our increasing electrified energy system alongside our growing population will continue to increase the likelihood of man-made fires.

Public Education: Continuing to provide resources for public education on forest fire prevention is also important. We should be reinforcing the reality that human influence is responsible for most of the forest fires we’re currently struggling against.

This list is not exhaustive, and there are other important solutions. But hopefully, these examples serve to broaden the discussion around the solutions to combat forest fires in North America.

Let’s Stop Laying Blame at Climate’s Feet 🦶

Climate change mitigation is unequivocally important. But using climate change as a scapegoat in the discussion is unproductive.

As we’ve discussed, the relationship between climate change and forest fires is nuanced. And while our influence on the earth’s climate is certainly impacting forest fires, so is ineffective forestry management, and our increasingly electrified energy system.

Michael Shellenberger, an established environmental advocate, provided a fitting conclusion in his latest book titled Apocalypse Never.

“The bottom line is that other human activities have a greater impact on the frequency and severity of forest fires than the emission of greenhouse gases. And that’s great news, because it gives Australia, California, and Brazil far greater control over their future than the apocalyptic news media suggests.”

If you want to learn more about forest fires, here are some of the best resources I’ve found on the topic:

Article: The relationship between forest fires and climate change (Nat Geo)

Article: Underfunding of firefighting units (Washington Post)

Movie: On the danger faced by firefighters (Only the Brave)

Video: The basics of forest fire prevention (Youtube)

Podcast: On the world heating up, and heatwaves (The Economist)